The Digital India Act and the Strategic Partnership on ICETs

- Abhivardhan

- Mar 25, 2023

- 8 min read

The Information Technology Act, 2000 has been in force for over 20 years. The legal instrument governs the use of electronic documents and digital transactions in the country. The act aimed to provide legal recognition for electronic documents and ensure the security and privacy of digital information. The law has had several key provisions, including the establishment of the Controller of Certifying Authorities (CCA) to regulate digital signatures, the introduction of electronic contracts and digital signatures as legally binding documents, and the creation of an appellate body for cybercrime cases. At the time, the IT Act was considered a significant step forward in India's digital transformation. It created a legal framework for e-commerce, e-governance, and other digital activities, and paved the way for the growth of India's tech industry. However, over the years, the IT Act has become increasingly outdated and inadequate in addressing the challenges and opportunities presented by the rapidly evolving digital landscape. New technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and the internet of things have emerged, and cyber threats have become more sophisticated and pervasive. To address these issues and provide a more comprehensive framework for India's digital future, the government has proposed the Digital India Act. The proposed legislation seeks to create a new regulatory structure for emerging technologies and strengthen cybersecurity measures. It also aims to promote the development of a digital ecosystem that fosters innovation, entrepreneurship, and inclusive growth.

However, one has to reckon the fact that regulations and statutes work in sync with the economies they are used to govern. In the case of the IT Act and even the Digital India Act, it could be understood that the role of technology co-operation has been key to India's seemingly huge advances, both in regulatory governance and information economics. This explains the necessity of the US-India Strategic Partnership on Information, Communication and Emerging Technologies (ICETs) and its needed elevation in early 2023. Thus, India's relationship with the United States has been important to shape its mettle as a technology power. In this article, I have explored how the ICET partnership and the upcoming Digital India Act would shape India's technology governance avenues.

Confronting Horizons of Technology 2.0 and Technology 3.0 Together

The proposed Digital India Act represents a critical milestone in India's digital journey as the world grapples with the growing power and influence of Big Tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple. These companies have amassed vast amounts of data and are using it to shape user behaviour, influence political outcomes, and dominate markets.

The Digital India Act is aimed to address the challenges posed by these Big Tech companies by introducing measures to promote competition and protect user privacy with unwavering determination. Moreover, the Digital India Act aims to ensure a level playing field for all players in the digital ecosystem, including startups and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Now, what one can understand is that it is these big technology companies whose actions in corporate governance, digital connectivity, intellectual property rights and business ethics, have led governments across the world to build their own regulations and standards, not to just hold them to account, but also estimate how they can develop better regulatory infrastructure keeping up with the changes that ICETs undergo.

To be fair, the European Union came up with the General Data Protection Regulation and then still is deliberating among countries and stakeholders about the impact of the proposed Artificial Intelligence Act. Despite these regulations being sophisticated and too specific on civil liability, digital rights and market economics, they are maximalist in nature. Similar concerns were raised by the US Chamber of Commerce.

There are other issues which exist as well. Even when we analyse the state of regulation of big technology companies in the United States, the multi-sector impact that big tech companies may produce remains to be properly assessed. Alexander Jones explains this problem by taking transparency as a regulatory expectation in an article for International Banker. Jones argues that while authorities may impose requirements of disclosure and reporting, they may not be that effective due to the following reasons:

cross-sectoral and cross-border nature of big tech activities;

centrality of data flows and cutting-edge technology within the digital-platform ecosystem;

large number and variety of entities within big tech groups, arranged in complex, layered organisational structures, making it challenging for financial authorities to understand their inner workings deeply.

In addition, the institutions involved in making these technology products, systems and services are capable in creating complicated and inexplicable derivatives of the product/service originally provided which further complicates things when rights and restrictions of use related to proprietary information are adjudicated. In fact, these sub-sets, sub-products, derivatives and other possible knock-offs or modulations drive the trajectory of the Web2 and Web3 industries. There are certain Web3 products and solutions which on their own fail (like Metaverse), but their concept is used in the existing Web2 paradigms, quite interestingly. Spatial commerce by Shopify is one such example. These issues, in my view should be dealt by the proposed Digital India Act with a soft-touch regulatory outlook, which is suggested for a digital markets law subject to discussion through the Competition Commission of India.

The Proposed Digital India Act as of March 2023

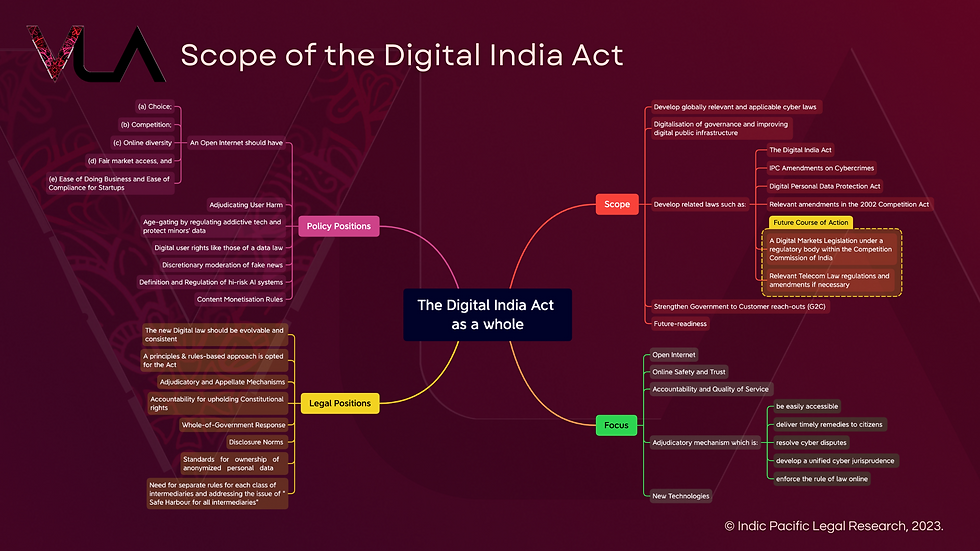

A draft proposal of the Digital India Act, not containing a draft of the Act itself was released. The presentation is discussion-based and explains what issues are necessary to be covered as a starter. Here is a representation of the points of focus with respect to the Digital India Act:

Now, this Act is well-expanded and all-comprehensive if we look at its policy and legal positions. The Act is a part of the cyber law infrastructure that the Government of India intends to build up. This would for sure require a Digital Data Protection Act and some key amendments in our telecom regulations (I propose), the Competition Act, 2002 and the Indian Penal Code, 1860. It would also require to develop a Digital Markets Law which consists of a sector-centric regulator under the Competition Commission of India. We have to also consider the Draft Telecom Bill which is subject to public comments and consultations. Strengthening digital public infrastructure and Government-to-Customer Engagement (G2C) is a quite interesting thing to look out for. Then, developing an adjudicatory mechanism is an appreciable move, which focuses to develop a unified cyber jurisprudence. Since cyberspace is the basis for the digital world or the information economy, the approach seems quite clear.

The Open Internet as per the Digital India Act

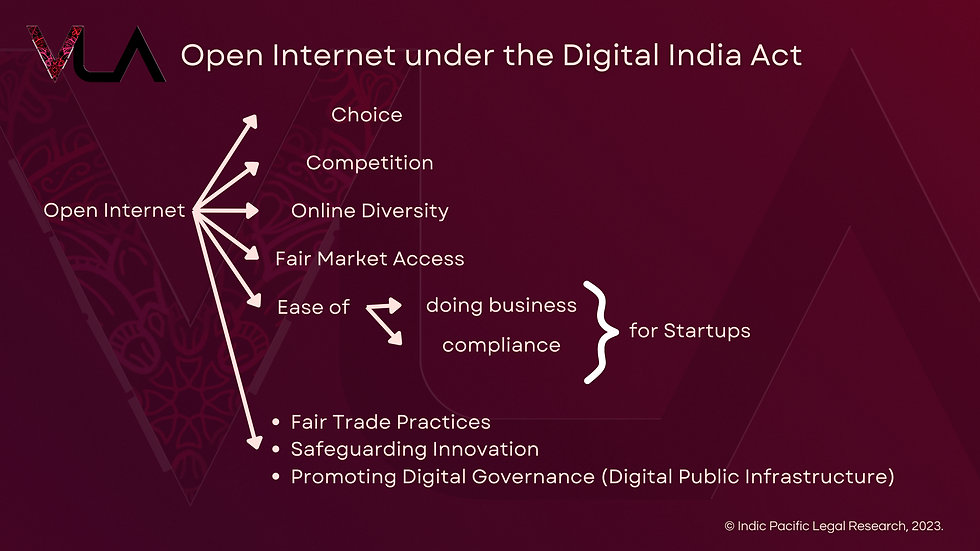

I find the way Open Internet is categorised interesting. Let us unfold how Open Internet is categorised and further elaborated upon.

So, the first category - Choice is important. It reflects the right to choose and use throughout cyberspace, laying the basis of an open internet as per the Act. Competition, the second category is in sync with Choice where Online Diversity may be related to the equality of opportunity one may get in digital opportunities, discourses and systems. That may also be related with the digital rights that this Act would provide. That leads us to Fair Market Access and Ease of Doing Business & Compliance. There is nothing new, but a clear categorisation was required in Indian law, which this Act may achieve for good.

Whole-of-Government Response and Digital Public Infrastructure

It is an imperative to realise that technology governance can be categorised into 3 folds of public interest and policy concern:

Digital Public Infrastructure

Regulatory Institutions

Judicial Institutions & Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

As a starting point, the proposal seems clear that a Whole-of-Government Response would be taken as the key element of this Act's approach of technology governance. As the proposal states:

Whole-of-Government Response for a unified, coordinated, efficient and responsive governance architecture including an effective appropriate government structure, a dedicated inquiry agency and a specialised Dispute resolution/ adjudication framework

It means that when any technology or data-related issues could come up, the Digital Public Infrastructure backed by a government structure and a dedicated inquiry agency would be on the run to help aggrieved parties. It is also appreciative that a dispute resolution & adjudication framework would be decided in the Act. This itself explains that the Government's focus on shaping technology governance is comprehensive.

Standards for ownership of Anonymised Personal Data

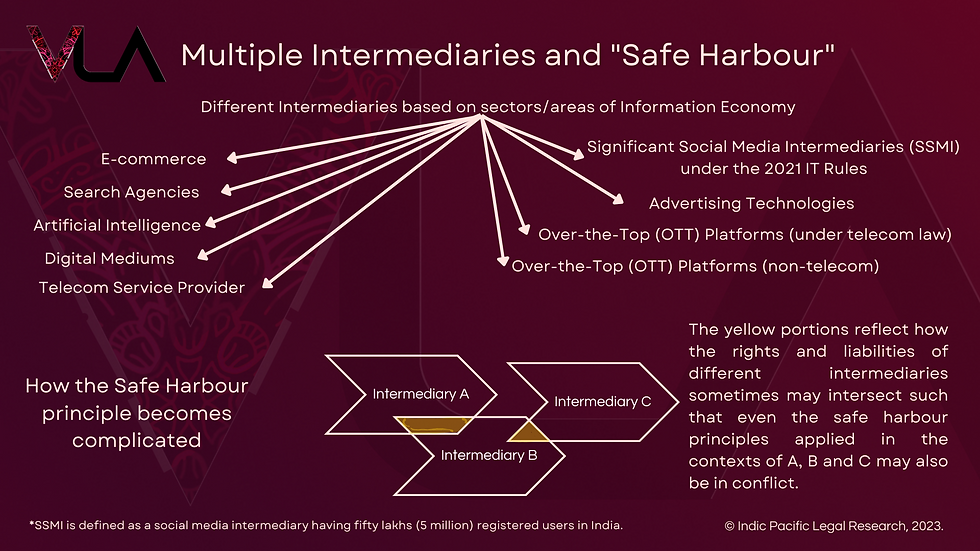

This is also one of the most important areas of concern, which the Act may cover, apart from disclosure norms. It would be intriguing to seek how the Government would try to determine ownership standards for Data Intermediaries. There is another concern which may help in shaping Ownership Standards - the Safe Harbour Principle and having different kinds of intermediaries.

The yellow portions in Figure 3 reflect how the rights and liabilities of different intermediaries sometimes may intersect such that even the safe harbour principles applied in the contexts of A, B and C may also be in conflict. Now, a safe harbour clause inserted in any legal instrument implies certain context-based rights on the use and platforming of third party data and information. Imagine how complicated it could get, from a legal perspective where rights, liabilities and responsibilities of 3 intermediaries, for example could get in conflict with one another, both respectively and as a whole. Taking this into consideration, the Government of India, in recommendation, create principles of defining how certain product or service use cases lead to companies gaining the status of intermediaries and what kinds of intermediaries may be relevant or not. It may seem a complex question to answer at first. However, a complex adaptive method could be adopted to interpret and define such things by focusing on the genealogy and economics of innovation in such technology products and services. That makes the picture way clearer. Maybe, this Act would address this issue broadly. That would help in designating classes of intermediaries, both which are made in the past, and those which could be made in the future.

Conclusion: the ICET Partnership and its Impact

The fact that the Act is aimed to be made all-comprehensive explains how important the US-India Strategic Partnership on ICETs is. Most importantly, here are the points of critical importance from the Fact Sheet by the White House on the Strategic Partnership on ICETs, when it comes to the Digital India Act:

Drawing from global efforts to develop common standards and benchmarks for trustworthy AI through coordinating on the development of consensus, multi-stakeholder standards, ensuring that these standards and benchmarks are aligned with democratic values.

Launching a public-private dialogue on telecommunications and regulations.

Advancing cooperation on research and development in 5G and 6G, facilitating deployment and adoption of Open RAN in India, and fostering global economies of scale within the sector.

Let's take these points into consideration. Now, India's technology partnership with both the United States and the European Union have different meanings and purposes. With Europe, India aims to bridge gaps on attaining sophisticated inter-regulatory channels for digital connectivity. With the United States, the focus is on innovation and economic activities to bridge gaps on competition law matters. The reason is that India's competition law approach is tilting to incline with the US approach, from a market point of view. Europe and China's separate maximalist approaches of technology regulation (and even market regulation) could enable the United States and India to become significant technology regulators and enhance their regulatory sovereignty differently. Both the countries are addressing tech regulation dilemmas and even competition law issues as technology sovereignty is becoming essential day by day. The difference is that the United States is a long-run player in this which is not even able to take calculated decisions on regulating and banning Tiktok and related apps and companies. India, however, has developed a much clear precedent by banning Tiktok and as an emerging economy, it has a lot more leverage as compared to the US to shape market and tech regulations with a unique rules-based approach.

The way the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission in the US have conflicting approaches to antitrust is not faced in India, similar to how banks and stock markets are regulated in the US, considering the crisis unfolded due to the fall of FTX and the Sillicon Valley Bank. Indian regulators in finance, market and tech have been more conscious of such realities and while the technology partnership in multiple folds is modifying its embodiment amidst the fears of recession in the US, the India-US partnership has an economic edge over other regulatory players to act differently. This is where the Digital India Act become a globally relevant instrument and even help the Global South countries to develop their own regulatory standards comprehensively. While the US is betting on dealing with the risks at its best, even by learning from Indian regulators in certain aspects, India has a much open ground to incentivise the best regulatory environment for investors, start-ups and innovators under the Act.

コメント